One of BMW’s great strengths turns out to be an unexpected versatility.

Many have scoffed at the Bavarian firm’s extra-mainstream approach to motorcycle design, the main elements of which were established 54 years ago, but it seems to work for them — and in surprisingly diverse fields.

BMW’s early image in this country was that of a stodgy tourer; quiet, comfortable and reliable but offering no more excitement than that inherent in any form of two-wheeled travel.

Yet BMWs have won numerous championships in sidecar racing, knobby-tired versions have earned ISDT Gold Medals, and BMW has been preeminent in AMA Superbike road racing.

The present BMW continues the tradition in the sense that it, too, is quiet, comfortable and reliable; it adds to those virtues a very nice dash of sporting character, and sporting performance.

The Boxer Engine

BMW’s formula for performance always has been to treat crank stroke, numbers of cylinders and curb weight virtually as constants, and add muscle with displacement increases gained with cylinder bore diameter.

That’s most of the difference between BMW’s 750 and 900 (bores of 82mm and 90mm, respectively) and the same path was taken in the creation of the new R100/S we’ve just finished testing.

Cylinder bore in the new BMW “thousand” has been increased to 94mm, bringing its displacement up to an even 980cc, and this would not have been possible without the margins of strength added in the great redesigning that was done for the 1970 model year.

The Seventies BMWs tell us, unmistakably, that their makers still prefer the straightforward and simple in engine design. The new BMWs still have just two cylinders, in the balanced horizontally-opposed configuration that has for so many years been a BMW trademark. And the valves are still opened by means of rockers and long push rods reaching out from a single, centrally-located camshaft.

There’s a two-throw crank, still supported in only two main bearings, and simple automotive type connecting rods with split caps and plain insert bearings. But that crankshaft is made from a tough, alloy-steel forging and its mains aren’t much farther apart than those in a Honda CB750.

The crankcase itself is so compact that it can’t help being strong, and though the whole assembly offers none of the multiplicity of camshafts, etc., so adored by motorcycling’s technoids, the truly important things have been managed very neatly and that’s why, after a half-century, the BMW flat-twin is alive and in splendid health even today.

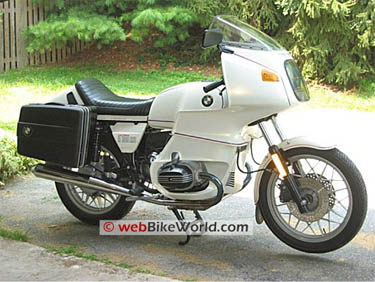

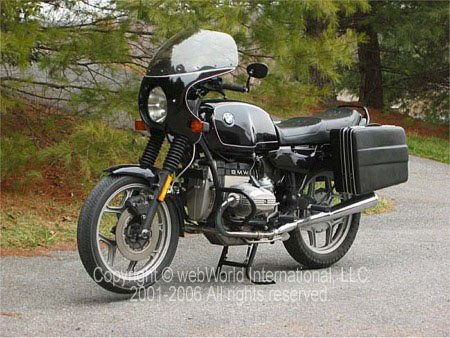

The BMW R 100 S

The R100S’s growth from a 600 has not been entirely without problems, most of which seem to have been recognized and solved.

One particular difficulty came from the very compactness of crankcase that provides the engine its strong foundation. Due to the opposed motions of the BMW twin’s pistons and its high crankcase compression ratio there always has been in it a tendency to huff, puff, and blow its oil out on the ground.

In the R100/S’s immediate relatives this huffing was controlled with a simple spring-loaded flapper disc, which kept the engine from inhaling a volume of air equal to its own displacement with each 180-degree rotation of its crank and then exhaling much the same volume of oil mist when the pistons returned to bottom center.

The flapper disc permitted only the exhale, which didn’t amount to much when not preceded by an inhale–in the smaller-displacement BMWs.

Unfortunately, there proved to be so much huff-and-puff in the 900 that the simple flapper arrangement began to lose control of the situation when some rider took his R90/S on a long, fast run. Under those conditions a lot of oil droplets would escape past the flapper valve, sneak down the short hose leading to the air filter/chamber, and find themselves being eaten by the engine they were supposed to lubricate.

BMW realized that if this could be a problem at the 900cc displacement level it would be one with the engine stretched to l000cc. They fixed it before it happened by casting a small baffle chamber in the crankcase–which holds the case fumes long enough, before they go out the flapper, to let oil droplets collect in the chamber’s floor and drain (via small holes) back to the sump.

The 900 had also demonstrated that a BMW clutch could be brutalized into slipping, and that, too, could have been a more serious problem in the R100/S. The new clutch has been strengthened, without added weight, by thinning the flywheel and adding thickness to the pressure plate.

BMW also changed the numbers of teeth on the flywheel rim and starter pinion for a greater reduction ratio, which the starter needed to handle the bigger engine without straining. (For those mornings when it’s really too cold for riding a motorcycle, but you do it anyway.)

The R100/S engine makes its connection with the bike’s rear wheel through the same five-speed transmission, U-jointed shaft and final drive assembly used in the other currently-produced BMWs. The slash-S designation means it’s a Sport, so this R100 has an abbreviated faring, dual-disc front brake, low bars, racer seat, electric clock and voltmeter.

Frame and Features

Those sporting/luxury features you’ve seen before in BMWs, but this year’s bike includes one highly important feature you can’t see at all: its frame has been stiffened. The various frame tubes’ placement and external dimensions are as before; the tubes do have thicker walls, and thus greater rigidity, and though you can’t see this difference the change in feel is unmistakable.

Recent BMWs have handled fairly well, with just a touch of rubbery imprecision in the hands of a rider who likes to force fast attitude changes by levering away at the handlebar. The stiffer frame has tightened the BMW’s response, made it more precise and better able to live up to its “Sport” name

Ultra-soft fork springs and powerful brakes have given BMWs a habit of kneeling, like an elephant inviting its mahout aboard, when being stopped fast. The R100/S does the same trick, but without the old disconcerting abruptness. The bike provides the same 8.5 inches of front suspension travel as an R90/S, and has the same two-rate springs.

Nose-dive, which cannot be eliminated without compromising one of the BMW’s best features–its smooth ride–has been brought under better control by the elimination of one bleed hole in each fork damper assembly.

This measure has introduced a stronger resistance to rapid fork compression, with hydraulics instead of stiffer springs. The R100/S’s rear suspension has German-made Boge shocks, with soft springs and well-controlled damping, that are carryovers from the R90/S.

Joining with others in anticipating emissions standards for motorcycles, BMW has fitted the R100/S with 40mm Bing constant-vacuum carburetors instead of the 38mm Dell’Orto pumpers that graced the R90S’s cylinder heads The Dell’Ortos had accelerator pumps, which provided instant response to throttle–and a sizable whiff of unburned hydrocarbons with each response.

Although the Bing carburetors may be a trifle less responsive they offer a fuel economy emission advantage in their ability to deliver a finely-atomized, clean-burning mixture at all engine speeds and throttle settings.

The R100/S also has a slightly taller rear axle ratio than the R90/S (2.91:1 instead of 3.0:1) and that may reflect concern about emissions and noise. But the change in gearing is about what you’d expect from a firm whose engineers have direct experience on Germany’s no-speed-limits autobahnen. BMW’s most immediate customers can and do, ride a hundred miles or more at speeds close to 100 mph, and they prefer long-legged gearing.

Starting the R100S

We once made an unkind, slightly off-color remark about BMW’s ignition/lights-switch key being too bulky to be conveniently stowed in one’s pocket.

The jest seems to have been taken seriously: BMW’s new key has a bottle-cap knob, which has been hinged to fold so that it and the key blade form a flat-profile object when dropped into a pocket. You turn the knob perpendicular with the blade when inserting the key in the switch, and when in place it looks more the fixed knob of a switch than something you can withdraw and carry away.

The key can be turned to a parking position, which energizes the bike’s taillight and a low-wattage bulb in the headlight nacelle but not the ignition. With the switch turned to its ignition-on position you get a veritable Christmas tree effect from the instrument cluster, which has warning lights for the brake fluid level, neutral, oil pressure, generator output, and turn signal operation.

The Bing-equipped R100/S starts quicker and with fewer hot/cold quirks than the R90/S which ran very well but always played a little game of “guess what I want” when its starter button was punched. Some of the improvement probably comes with the change in starter reduction gearing, which takes some of the strain off the electric starter motor, but much of it seems a function of improved carburetion.

There’s a choke lever located on the left side of the engine’s tall air cleaner housing, and it’s needed only for cold starts. You use the choke for only moments, because the engine quickly warms enough to run without rich-mixture assistance–and it fires, hot or cold, with just a tap of the starter button.

People have come to expect the BMWs will be extraordinarily quiet, and the new R100/S isn’t going to disappoint them. At low engine speeds there’s a blurred string of mellow thuds from the exhaust tips, and the faintest kind of push rod clicking, but that’s about all you hear.

Intake drone is squelched by BMW’s novel induction system, which pulls air into the cast aluminum pagoda above the crankcase, routes it past the starter motor and into the filter element housed there, and sends it out through long hoses to the carburetors.

It’s such a long and winding trail from the carburetor mouths to the open air that the noise just gets lost somewhere along the way. When the engine speed is up above 3500 rpm the push rod clicking turns into a clatter, but the BMW never indulges in the nervous gnashing that has been characteristic of big multis.

Controls

A redesigned and splendidly effective Magura lever is used for clutch actuation. It has done a lot to eliminate the heavy, finger-straining feel of previous BMWs, and the tendency of their diaphragm-spring clutches to engage with a grab. And the new clutch proved equal to the increase in engine displacement, refusing to slip or chatter even when in constant and ungentle use.

BMW’s tradition unfortunately includes a transmission that does not always shift as smoothly and easily as it should. You can’t always get first gear, from neutral and with the bike stopped, without fanning the clutch in and out of engagement to keep the cogs spinning.

Shifting up or down through the lower three ratios also is uncertain work. It all goes fairly well if you don’t try to hurry shifts, but the heavy flywheel and clutch assembly combine with the big ratio differences in first-second, second-third shifts to produce a tendency for the shift dogs to miss engagement–and to make a big clunk when they do engage

On the Road With the BMW R100S

Another less-than-desirable characteristic of the BMW is its response to engine torque reaction. With the engine’s crankshaft being in fore/aft alignment in the motorcycle, the reflected torque applied at the engine mounts causes the whole motorcycle to sway sideways when you blip the throttle.

What happens here is that when the pistons accelerate the crank and flywheel clockwise, all of the surrounding structure is subject to a reaction force that twists it counterclockwise.

You get the same forces in motorcycles with crankshafts disposed across their frames, but in those it becomes a force (usually) acting to lift their front wheel. You should understand that this is a force separate from the engine’s driving torque; it is one produced by the inertia at rotating masses, and thus exists only when there is a change in engine speed.

So you don’t get any torque sway when you’re just cruising along, and even when you speed or slow the bike it usually isn’t there in a magnitude great enough to be felt. It’s only when the engine speed changes rapidly, as during a downshift, that you can feel it at all.

Mostly the torque reaction is just the swaying you get when you’re stopped and blipping the throttle to impress the blonde in the convertible. There’s more of it with the big R100/S engine; it’s still not enough to count for much under anything like normal riding conditions.

A vastly more consequential phenomenon you feel in the BMW is the attitude change produced by the rear suspension’s own set of torque reactions. Torque applied at the rear wheel via the drive shaft, pinion and ring gears reflects back as a force that tries to shove the wheel downward away from the chassis.

When, as usually is the case, the wheel already is down against the road the chassis gets jacked upward–and the jacking affect is very pronounced when engine torque is being multiplied through the transmission’s lower gears. Much the same thing occurs when the bike’s throttle is closed, except that engine braking reverses the torque and the chassis is pulled downward.

All shaft-drive motorcycles are similarly affected; the BMW’s light weight (about 100 pounds less than its displacement-equals) and ultra soft suspension cause this phenomenon to show up particularly strongly. Most riders aren’t bothered by it; it’s an affliction only for those who ride on the ragged edge–which it makes a little more ragged.

The fact that the R100/S was built for fast travel on the open road makes it a bit awkward in town. It gets some help in dealing with urban conditions from its wide-ratio transmission, but the slow, stability-oriented steering and semi-cafe racer riding position are poorly suited for trips down to the local supermarket.

The R100S is at its best on long, fast hauls, where it can get into its long-legged stride and where the handling is a delight. Out on the open road the BMW R100/S definitely is the most comfortable sports bike we’ve tried, and with all its sporting bias it remains one of the most comfortable for ordinary touring.

The Sport has particularly good handling on mountain roads. There is a little too much fore/aft pitch when you come off the throttle and use the brakes, and vice versa, but a rider who’s good enough to be pressing matters hard enough to turn this into a problem will be good enough to deal with it. As noted before, the soft suspension contributes to the changes in chassis attitude, but what you lose to that is regained by the absence of jolt and clatter.

Tires

Our R100/S was fitted with compromise-compound Metzeler tires, and compromise inner tubes. The tubes are made of a natural rubber, which has a lower density than a synthetic and allow air to escape slowly right through their walls (we noted a four-psi pressure loss in two weeks).

The natural rubber tubes’ habit of losing air isn’t pleasing, but before you think of switching to synthetic tubes please consider what happens when a nail comes poking through the tire: the natural rubber is so soft it clings to the nail, continues to hold the air fairly well, and gives you a chance to feel the tire going flat long before it gets there; synthetic tubes tend to tear when punctured and deflation is much more rapid.

The Metzeler tires themselves also are a mixture of the desirable and the unfortunate. Their tread compound is quite hard. which means they’ll last a lot of miles–but don’t represent the final word in cornering power.

BMW has chosen these Metzelers because they feel, and probably correctly, that the tires provide their typical customer with all the adhesion he’ll use and give him the maximum service life. Customers who disagree with that policy can fit a set of stickier tires and expect to replace them at more frequent intervals.

Some of our test riders complained of rubbing their shins on the BMW’s rear-facing carburetors, which do extend back fairly far in the direction of the foot pegs. These complaints did not, as you might expect, follow rider size–with the tall and lanky doing most of the complaining. Rather, it seemed to be a function of riding style: everyone was comfortable just cruising along but some riders like to slide their weight forward before attacking corners and some slid too far.

On the other hand, none of us (well, there was one but he’s weird) liked the small diameter handlebar grips, and nobody had a kind word for the throttle action, which had a heaviness made all the more aggravating by the grip’s small size.

The bar-mounted signal and beam switches are an oddity for us (BMW’s flip vertically; (Japan favors the horizontal)) but we sometimes ride a half-dozen motorcycles in a single day. Those who own BMWs will get used to the vertical switching, and they’ll appreciate the nice, crisp switch action.

If you didn’t already know, the R100/S will tell you that bigger is not in all ways better. The one-liter engine has a more pronounced torque-pulse vibration than last year’s 900, which was not as smooth as the 750, and can be made to settle down and behave like smaller BMWs only within a narrow range of engine speeds and throttle positions. The bigger pistons may even have made some contribution to the overall dulling of the BMW’s willingness to respond snappily.

Yet it’s obvious why BMW has gone out to close to a liter of displacement: to maintain a performance level while complying with ever-stricter noise limitations, and with impending emission control requirements. They’ve done better than simply “maintain.”

Conclusion

The R100S is the first BMW in Cycle’s history, and we suspect BMW’s history, that has covered the quarter-mile in less than 13 seconds. It ran a 12.97 sec. quarter at over 103 mph, putting it in the rather elevated company of the KZ1000, the Honda GB750F2, and the GS Suzuki 750 as the industry’s only current 12-second offerings.

When you add for this and subtract for that you get a total that says the R100/S is every inch a BMW and every inch a Sport, but it’s hard to come up with anything that says the R100/S is actually better than the R90/S. It’s different, and it’s newer, it’s faster, and it’s more expensive; we’re not at all convinced that it’s a complete improvement.

Be that as it may, the R100/S is good, and it surely hasn’t stopped being a BMW. It still gives you a headlight that’s about as good as motorcycle lamps get to be, and it still provides its rider with the best set of tools he’s likely to see.

It even has all the quirky but totally effective BMW traits, like the drilled discs up front that make a subdued buzzing when clamped by the calipers–but aren’t bothered by streaming rain and don’t squeak. It’s been changed, but remains completely a BMW: fast, quiet, comfortable, very expensive and utterly unique.

CYCLE (May 1977)

| 1977 BMW R100S Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Suggested Retail Price | $4,195 |

| Tire, front | 4.0018 in. Metzeler |

| Tire, rear | 3.25-19 in. Metzeler |

| Brake, front | 1.375 x 10.24 in. x 4 (35 x 260mm x 4) |

| Brake, rear | 1.18 x 7.87 in. (30 x 200mm) |

| Brake swept area | 111.7 sq. in. (720.7 sq. cm) |

| Specific brake loading | .6.0 lbs./sq. in. @ test weight |

| Engine type | Opposed four-stroke twin, OHV |

| Bore and stroke | 94 x 70.6mm (3.70 x 2.780 in.) |

| Piston displacement | 980cc (59.8 cu. in.) |

| Compression ratio | 9.5:1 |

| Carburetion | 2, 40mm, Bing CV |

| Air filtration | Dry paper |

| Ignition | Battery and coil w/points |

| Rake/Trail | 280/3.5 in. |

| Mph/1000 rpm, top gear | 17.7 |

| Fuel capacity | 24 liters (6.3 gal.) |

| Oil capacity | 2.25 liters (2.4 qts.) |

| Transmission oil capacity | 0.8 liters (.85 qts.) |

| Electrical power | Alternator, 240 watts |

| Battery | 12V-28AH |

| Primary transmission | Helical gears |

| Secondary transmission | Shaft, spiral-bevel gears |

| Gear ratios, overall | (1)12.8(2) 8.32 (3)6.02 (4) 4.86 (5) 4.37 |

| Wheelbase | 147.3cm (58 in.) |

| Seat height | 80cm (32 in.) |

| Ground clearance | 16.5cm (6.5 in.) |

| Curb weight | 230kg (507 Ibs.) |

| Test weight | 302kg (667 Ibs.) |

| Instruments | 140 mph speedometer w/tripmeter, tachometer, voltmeter, clock |

| Standing start 1/4-mile | 12.974 sec. @ 103.32 mph |

| Average fuel consumption | 40.5 mpg – (43 mpg max., 39 mpg min.) |

| Speedometer error | 30 mph, actual 26.30; 60 mph, actual 54.24 |